Employee Stock Options: What You Need to Know

If you have ESOs, learning how to navigate them is crucial. Maximize your earnings by reading this guide.

Employee stock ownership was traditionally reserved for company executives, but has recently become a more mainstream benefit for the average employee. According to an article from the National Center for Employee Ownership (NCEO), employee stock ownership plans currently cover over 14 million participants.

One main type of asset that companies (especially small firms and startups) like to issue is a stock option.

What’s an Employee Stock Option?

An employee stock option (ESO) is an asset that gives its holder the ability (but not the obligation) to buy a certain number of company shares at a given price, within a certain period of time. It’s similar to a listed call option, except that it’s issued by the company and therefore cannot be sold on the market.

The underlying asset of an ESO is company stock, meaning that they give employees the opportunity to make money by locking them into a price at which they’re allowed to purchase stocks, giving them a discount if the price in the market rises above that level.

There are a few reasons why an employer may decide to grant options for its employees. Unlike cash benefits, stock options tie an employee’s motivation directly to the success of the company. It can also give them pride of ownership and provide a clear image of how much their contribution is worth to the employer.

How Do ESOs Work?

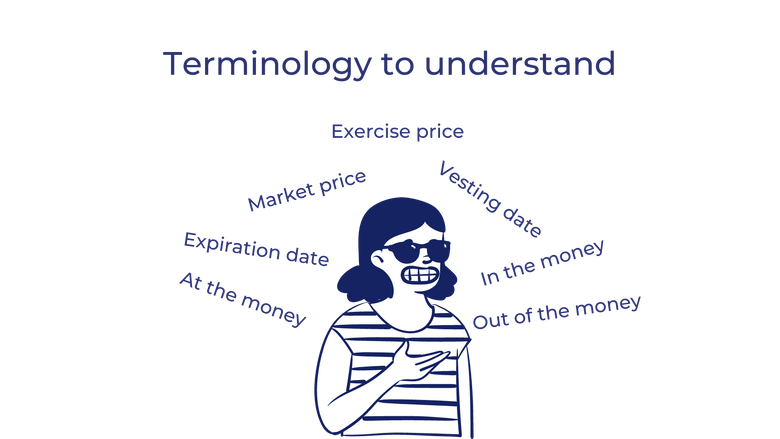

To think about how ESOs work, let’s go over some terminology:

- Exercise price (also known as strike price): the fixed price at which you’re able to buy/sell a stock

- Market price: the current price of the stock in the market

- Vesting date: when you can first exercise your options

- Expiration date: when you must exercise your options by

- In the money: if the option has intrinsic value (in this case, the market price is higher than the strike price)

- Out of the money: if the option doesn’t have intrinsic value (in this case, the market price is lower than the strike price)

- At the money: if the market price is equal to the strike price

Here's an example of this terminology in context, showing how ESOs play out:

Imagine your company gives you ESOs with a strike price of $15 on 100 shares and 10 years until the expiration date. The vesting date is in one year, at which point the market price is $25. At this point, your options are in the money, meaning that it would be profitable to exercise. If you exercise your options as soon as they vest, you can sell them right away to make a profit of $10 per share, or $1000 total. On the other hand, you can keep the stocks in your portfolio, or you can wait to exercise altogether until the stock price gets higher.

👉 Read next: What's a stock refresh and why should you care?

NSOs vs. ISOs

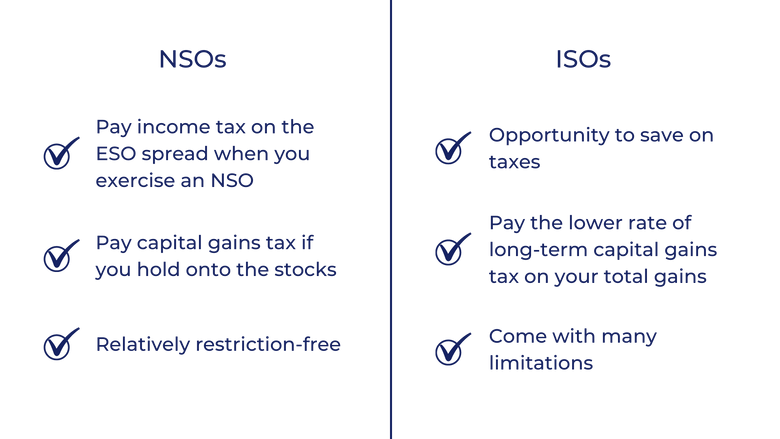

The two types of employee stock options are NSOs (non-qualified stock options) and ISOs (incentive stock options). While these two assets are pretty similar, the main difference is that ISOs come with special tax privileges, as well as a few restrictions.

Taxes

According to the NCEO, the tax difference between an ISO and NSO can be as much as 19.6% at the federal level. Here's why.

When you exercise an NSO, you pay income tax on the ESO spread-- that is, the difference between the market price and the exercise price. Going back to the previous example, you’ll pay income tax on ($25-$15=) $10 per share, or $1000. Then, if you hold onto the stocks, you’ll pay capital gains tax on the amount the stock has grown from the market price at which you exercised the option. Going back to the previous example, if you exercised your option on 100 shares when the market price was $25, and you sell them all when the market price rises to $50, you’ll pay capital gains tax on that profit of $25 per share, or $2500.

For ISOs, you have the opportunity to save on taxes as long as you wait to sell the stocks (a) at least two years after receiving the grant and (b) at least one year after exercising. In this case, you’ll have to pay the lower rate of long-term capital gains tax on your total gains from the sale. So if you exercise your options (with a strike price of $15) at $50 for 100 shares, you’ll only have to pay long-term capital gains tax on $35 per share, or $3500 total. However, the exercise spread of ($25-$15=) $10 per share will be taken into account when calculating your alternative minimum tax.

Restrictions

NSOs are relatively restriction-free: they can be granted to anyone (consultants, external directors, contractors, etc) and can even be transferred to others.

ISOs, on the other hand, come with many limitations. They can only be issues to employees and can not be transferred to others. There’s also a $100,000 limit on the aggregate grant value of ISOs that vest in a given calendar year. And after leaving a company, an employee can only retain ISO benefits if they exercise them within three months after termination.

The Risks of Employee Stock Options

They may become worthless

The good thing about options is that you can’t really lose money. At worst, if the market price never rises above the strike price, you never exercise them, and they’re worthless. However, this is still an unideal and entirely feasible outcome. It is especially possible in a startup context: if you're holding options and the company goes under, the assets become worthless. Even at a public company, the stock could collapse, the market could tank until the expiration date, or you could quit or be terminated and lose the options before they vest. In other words, options can be a fun perk, but be wary of stock options that make up a large portion of your compensation package. It’s almost never a good idea to take a lower salary in exchange for ESOs.

They can be difficult to navigate

There are a lot of considerations that go into ESOs. Not only do you have to think about the best time to exercise, but you also have to think about what to do after. Many experts advise selling right away to invest in diversified stock or index funds, as it can be risky to keep more than 10-15% of your portfolio tied to a single company. However, if you have a strong feeling about your company’s success and want to hold onto your shares, that’s your risk to take. Regardless, it’s important to be informed about the implications of your decisions beforehand.

👉 Landed a new job with ESOs in your offer? Schedule a call with Candor to make sure you're getting paid what you're worth.

The information provided herein is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to provide tax, legal, or investment advice and should not be construed as an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or a recommendation of any security by Candor, its employees and affiliates, or any third-party. Any expressions of opinion or assumptions are for illustrative purposes only and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results and the opinions presented herein should not be viewed as an indicator of future performance. Investing in securities involves risk. Loss of principal is possible.

Third-party data has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, its accuracy, completeness, or reliability cannot be guaranteed. Candor does not receive compensation to promote or discuss any particular Company; however, Candor, its employees and affiliates, and/or its clients may hold positions in securities of the Companies discussed.