Hedging Your Losses with Put Options

Put options can lead to a large profit, but they come risks to both buyers and sellers. Here's everything you should know.

This article will cover:

- What is a put option?

- How put options work with examples

- Types of put strategies

- How, when, and why put options are used?

- Risks of put options

What Is a Put Option?

Put options are essentially contracts that give the options trader the right but not the obligation to sell a specified stock at a predetermined price. Put options are often seen as the opposite counterpart of the call option, which gives the right to purchase a stock at a set price.

Purchasing a put option is essentially a bet that the stock price of a company will fall in the future, making it a bearish investment.

- The put buyer generally waits for the price to drop so that they can purchase the stock at that lower price and sell it at the higher strike price.

- Selling a put option, on the other hand, means anticipating that the value of the stock will either stay the same or increase.

Put options expire after a specified period of time, meaning that a put buyer expects the stock price to fall within a certain amount of time. This expiration date depends on the duration of the option contract, which can be weekly, monthly, or quarterly. Once the option expires, the buyer can no longer exercise the right to sell the underlying stock. On the other hand, the buyer is free to exercise the option any time before the expiration date.

A put option is a derivative because it “derives” its value from the value of the underlying stock. Like call options, put options can apply to multiple different financial instruments, including ETFs and bonds, but stock-related put options are the most common application.

How Put Options Work with Examples

Put options are generally sold in bundles of 100 shares. The price you pay for the right to sell the underlying asset is called the “premium,” and is calculated on a per share basis. For example, buying one put option, consisting of 100 shares, for a premium of $4 a share would cost you a total of $400.

Because you are only paying the premium as the put buyer, you do not necessarily own the underlying stock itself. You are merely paying for the contract—the ability to purchase the stock when it comes time to exercise the option.

At the money

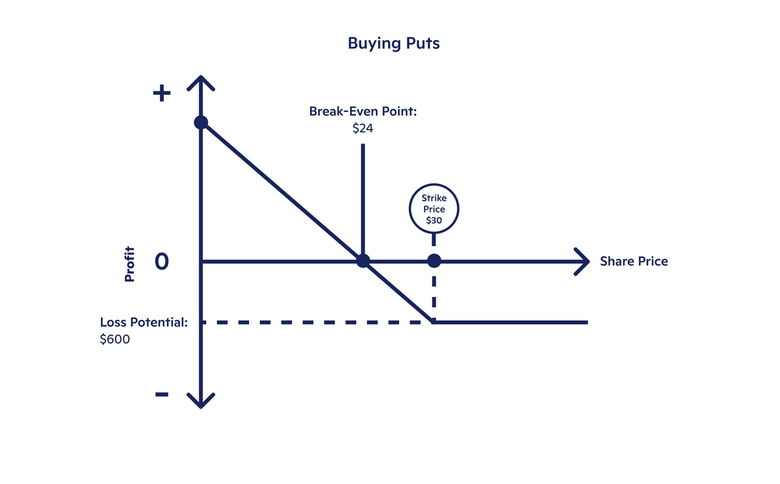

Let us consider an imaginary company called XYZ. Company XYZ’s stock is currently sitting at $30 a share. You want to buy one put option contract (100 shares) for XYZ at a strike price of $30. Because the put’s strike price is equal to the current market price, the option is said to be “at the money.” In other words, the put’s intrinsic value, or the amount of money it would return if exercised immediately, is $0.

But remember, if the option seller charges you a $6 per share premium, for instance, you pay a total of $600 for the put option. Therefore, exercising a put option that is “at the money” actually nets you a loss for the amount of premium paid for the contract.

Now imagine that the price of XYZ’s stock falls to $24 a share. At this point, you can choose to purchase 100 shares of XYZ for $24 each and sell them back at the strike price of $30. The intrinsic value of the option at this point would be $600. However, since you paid $600 in premiums for the contract itself, you would net $0. In other words, when the current stock price is $24 a share, you break even.

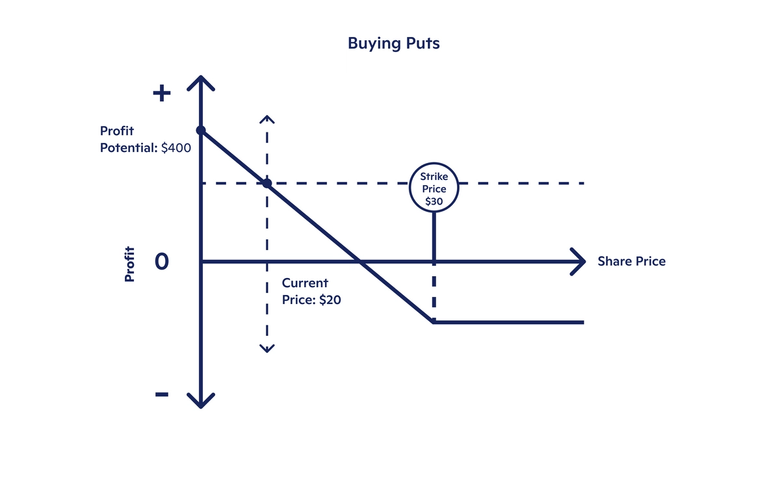

In the money

If XYZ’s stock falls even further to $20 a share, the put buyer is in luck. At this point, the total value of the 100 shares is $2,000. Buying 100 shares of XYZ for a total of $2,000 and selling it back at the strike price ($3,000 total) would mean being able to take home the difference of $1,000. Because you paid $600 for the contract itself, you’d find yourself profiting a total of $400. At this point, your put option is said to be “in the money.”

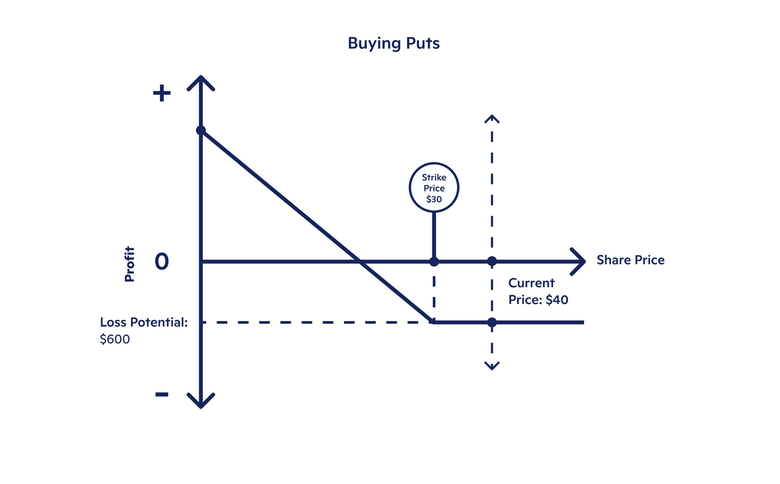

Out of the money

Finally, say that, instead of plummeting like you’d hoped, XYZ’s stock skyrockets to $40 a share. Exercising the option here would incur a loss of $1,000, since buying 100 shares would cost you $4,000. The option is “out of the money.” Instead of taking this loss, the smarter course of action would be to allow the contract to expire without exercising it. Remember, you aren’t required to exercise your option. Instead of taking that $1,000 loss, you simply forfeit the $600 in premiums and walk away.

4 Types of Put Strategies

1. Long Put

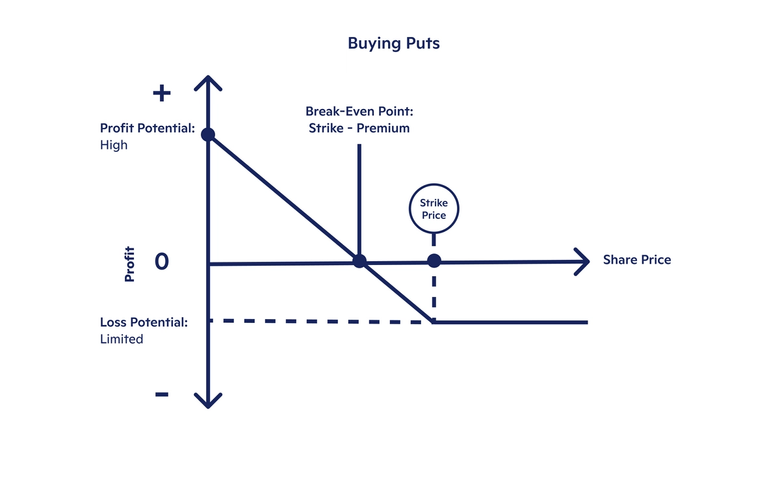

A long put is the most traditional of put options trading strategies. Investors who adopt a long put position are bearish on the underlying security. In other words, they expect the value of the underlying stock to depreciate in value in order to capitalize on their ability to sell the stock at a higher strike price.

A long put position is attractive because it allows the investor to pay a smaller upfront cost—the option premium—for a large potential gain. Long puts are also attractive because in the worst-case scenario where the price of XYZ’s stock skyrockets, the greatest amount of money the investor can lose is the premium. Remember, there is no obligation for the put buyer to exercise the option.

2. Short (Naked) Put

The short put, or naked put, can be seen as a position that opposes the long put. Rather than a bearish strategy that bets on the fall of a particular stock, the short put is a bullish tactic that expects the price of the underlying asset to stay flat or increase. And instead of purchasing a put option, a short put involves selling a put option.

Because you are selling the option, you want the option to expire out of the money so that you can pocket the premium without having to purchase the stock. Therefore, selling a put option for a stock that is more volatile is risky because it means a greater chance that the share price will decrease. Selling put options that are more out of the money might net you less in premiums because they are less likely to fall below the strike price, but they are much less risky.

Note that in a short put, the investor is exposed to hypothetically unlimited loss. Recall that the put seller is, unlike the put buyer, obligated to purchase shares at the strike price should the buyer exercise the option. Therefore, it is much safer to sell put options that are further out of the money.

3. Put Spreads

Put spreads are a more conservative strategy that involves balancing a purchase and a sale of the same security in order to cap losses. Put spreads can be bearish or bullish.

A bear put spread is often used when an investor expects a stock to fall, but only moderately. To execute a bear put spread, purchase a put option and sell a put option of the same security with a lower strike price.

A bull put spread works in a similar manner but expects a moderate gain in the stock price instead. Executing a bull put spread would mean purchasing a put option and selling a put option with a higher strike price. The maximum amount of money made would be the difference in premiums, in the scenario where the stock price rises above the higher strike price and both puts expire worthless.

Put spreads are helpful because the simultaneous purchase and sale of a put option offset each other, reducing the total amount of risk. The net amount of capital that needs to be spent on the transaction is also lower because of the opposing premiums.

4. Protective Put

A protective put is a strategy in which you hedge a long position in a stock. It is meant to protect a normal long position in a particular stock.

Purchasing a put option for XYZ for every 100 shares of XYZ owned, you effectively hedge your bets in the event that XYZ’s stock plummets. If the price of XYZ falls below the strike price of your puts, your options are in the money and the gains you realize from your options can offset the losses you see from the stock itself.

On the other hand, if the stock stays put or increases in price, the only loss to this strategy is the premium of the put options.

Using Put Options

How to Buy vs Sell

Put options can be bought and sold through various brokerage firms like TD Ameritrade and E*Trade.

Buying a put option involves paying a premium for the right to sell the underlying stock at a specified strike price. The amount of premium paid depends on various factors, including the actual price of the stock, the stock’s volatility, and the amount of time left before the option expires. These are all factors that influence how likely the put option will expire in the money. In the end, purchasing a put option is a bet that the stock price will fall.

On the opposite side of the transaction is the sale of a put option. Put sellers are paid a premium in exchange for the right to sell a stock at a certain strike price. The catch is that if the option buyer chooses to exercise the option to sell 100 shares at the strike price, the put seller is obligated to purchase those 100 shares. This could potentially mean a big loss for the seller if the strike price is far higher than the current market value.

The important difference is:

- The put buyer has the option to sell the stock at the strike price, but is not required to.

- The put seller is obligated to purchase the stock if the option is exercised. If the option is not exercised, however, the put seller is able to pocket the premium.

When to Buy vs Sell

Buying a put option is a bearish strategy. This means that the investor will only profit when the stock falls far enough below the strike price to make up for and overtake the amount of money paid in premiums upfront. So only buy a put option if you’re comfortable betting on this decline in stock price.

Selling a put option is a bullish move because the put seller makes their maximum profit if the option expires out of the money. Note also that the put seller can still make a reduced profit if the option buyer exercises the option at a market price that doesn’t fully overtake the premiums received. Still the option seller hopes for the stock involved to increase in value or at least stay flat.

Why Do People Use Put Options?

- Make money selling put options: If done carefully, selling put options can bring an investor a steady stream of income from premiums. More conservative investors can sell put options that are far out of the money to reduce the chance that the stock price will fall below the strike price. To take on more risk for more potential reward, you can sell options that are in the money or close to the strike price for a higher premium and bet that the stock rallies.

- Limited Downside: Using put options allows you to invest in a stock without actually having to own the stock. Put buyers only pay a premium, and in the worst-case scenario where the stock price skyrockets, the put buyer only loses that premium. This makes put options potentially more lucrative than short selling because a short position involves actually borrowing the stock involved.

- Protect Other Investments: Buying put options can be a good way to reduce any potential loss from a regular stock investment. Anyone from individuals to institutional investors can purchase a put option to reduce losses from a potential downturn in a stock’s price. If a stock falls dramatically in value, a put option for that stock would turn a profit, offsetting any losses. If the stock price rises, all you lose from the put option is the premium.

Risks of Put Options

Volatility

Volatility can be a double-edged sword for both the put buyer and seller.

For the put buyer:

- Stocks that move more have a higher chance of falling below the strike price, allowing the buyer to exercise the option and make a profit.

- However, this also means that the stock has a higher chance of rising far above the strike price, which would force the buyer to let the option expire worthless.

For the put seller:

- Generally speaking, the more volatile the stock, the higher the premium of the put option, so the seller is able to make more money off of premiums for a volatile stock.

- However, volatility means a higher chance that the stock will plummet, allowing the put buyer to exercise the option.

Unlimited Downside for Sellers

If done right, selling put options can be a reliable source of income.

🚩 However...

It is extremely important to remember that put option sellers are vulnerable to the possibility of unlimited losses if they are not careful. While a call option seller’s losses are capped because a stock’s price cannot fall below $0, a put option seller can theoretically lose an infinite amount of money because a stock’s price can simply keep rising.

Key Takeaways

Simply put, buying or selling put options can be a lucrative investment strategy, but it is essential to carefully consider your decisions in order to minimize losses.

Here are some key points to remember when it comes to “putting” your money into puts:

- Buying put options is a bearish strategy while selling put options is a bullish strategy. The former bets on a stock’s fall while the other hopes for that stock to either rise or stay flat.

- When a stock is below the strike price, it is “in the money,” and the put buyer can make a profit by purchasing the stock at the market price and selling it at the strike price. When a stock is above the strike price, it is “out of the money,” and the buyer is forced to let the option expire worthless, taking the premium paid as a loss.

- Put options allow investors to make money on a stock’s movements without having to pay the full upfront price of the stock. This means a put option has the potential for more return on investment than short selling.

- Put options in a stock can also be used to protect a long position in the same stock because gains from a put option can offset losses from a stock’s fall.

- Options traders must be careful when selling put options because selling puts has potentially unlimited downside, since a stock has no cap on its rise.

The information provided herein is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to provide tax, legal, or investment advice and should not be construed as an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or a recommendation of any security by Candor, its employees and affiliates, or any third-party. Any expressions of opinion or assumptions are for illustrative purposes only and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results and the opinions presented herein should not be viewed as an indicator of future performance. Investing in securities involves risk. Loss of principal is possible.

Third-party data has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, its accuracy, completeness, or reliability cannot be guaranteed. Candor does not receive compensation to promote or discuss any particular Company; however, Candor, its employees and affiliates, and/or its clients may hold positions in securities of the Companies discussed.