Index Funds: Low Cost Way to Invest for Beginners

Index funds can be a powerful tool to diversify your portfolio. The 5 types you should know, how to invest in them, and more.

Since the first index fund was created by Vanguard founder John Bogle in 1976, the financial vehicle has gained popularity in the portfolios of retail investors. With benefits including low costs and increased diversification, index funds are a great choice for many investors.

However, before buying index funds, you’ll want to know how they stack up against other investment options.

What Is an Index Fund?

An index fund is a type of mutual fund that tracks the holdings of a benchmark index, such as the Nasdaq Composite Index or the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA). Some investors may also use the term index fund to refer to exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

Although ETFs also track popular indexes, they’re structured a bit differently. Whereas mutual funds are priced and traded at the end of the day, ETFs can be bought or sold at any time, just like regular stocks. Additionally, many mutual funds set a minimum investment in order to buy in, whereas ETFs are traded as individual shares.

5 Types of Index Funds

Whereas buying index funds used to be known as simple investment products, it’s gotten more complicated over the years. As more companies have released index funds into the market, investors have gained an increasingly diverse range of options.

1. Traditional index fund

Traditional index funds track well-known market indexes, from domestic indexes like the Wilshire 5000 to global measures like the MSCI World Index. This structure works out for many investors, as they can share in the growth of the overall market.

The S&P 500 Index reflects the performance of 500 large-cap U.S. companies including Apple, Microsoft and Starbucks. Between 1991 and 2020, the index has seen impressive annualized returns of 10.7% before inflation, or 8.3% after. In turn, many investors get involved by buying S&P 500 index funds, including the iShares Core S&P 500 ETF (IVV) and the Vanguard 500 Index Fund Admiral Shares (VFIAX).

2. Sector-specific index fund

On the other hand, these index funds track the performance of companies within a single sector. In purchasing these funds, investors can also bet on particular industries where they anticipate seeing growth in the future, such as real estate or finance.

For example, technology index funds contain holdings in tech-oriented companies, including computer hardware, electronics and software as a service (SaaS). Index funds like the Vanguard Information Technology ETF (VGT) and the Fidelity MSCI Information Tech ETF (FTEC) both fall into this category.

3. Socially responsible index fund

Index funds can also be a great way to practice social activism with your bank account. One major downside to most index funds may be the lack of control over your investments. When you invest in a large basket of stocks, it’s unlikely that 100% of the portfolio will meet your ethical standards.

However, you can buy a socially responsible index fund that prioritizes sustainable companies. That way, you’ll be able to feel good about your investments while supporting ethical practices.

For example, the Vanguard ESG U.S. Stock ETF (ESGV) screens its holdings for environmental, social and corporate governance criteria. Additionally, it excludes companies from potentially harmful industries, including alcohol, tobacco, weapons and nuclear power. Other sustainable index funds include the Fidelity Sustainability Bond Index Fund (FNDSX) and the iShares MSCI Global Impact ETF (SDG).

4. Fundamentally weighted index fund

Many popular market indexes, such as the S&P 500 and Nasdaq, weigh their holdings by market capitalization. For example, in an equally-weighted index made up of 50 funds, each company would make up 2% of its portfolio. In a market capitalization-weighted index, companies with a higher total value will make up a greater percentage of the index.

Fundamentally weighted funds, on the other hand, calculate the size of each holding through alternative metrics. You may also hear them referred to as designer index funds. They’ll often focus on performance measurements such as revenue, dividend yields or book value.

For example, the WisdomTree U.S. Total Market Index (WTEI) is a fundamentally weighted index that takes into account each company’s past performance through its earnings over the four most recent fiscal quarters.

5. Leveraged index fund

Because of their diversified nature, many consider index funds to be a relatively safe investment compared to individual stocks. However, leveraged index funds don’t have the same reputation. Although they’re still made up of a large basket of stocks, leveraged funds use debt to increase their share. In other words, they’ll amplify movements in market price, making for a much riskier investment.

For example, the Direxion Daily Financial Bull 3X ETF (FAS) tracks the Russell 1000 Financial Services Index while multiplying total returns and losses at the rate of 300%.

Overcome the Pitfalls of Alternatives

Stock picking is risky

Many wealthy hedge fund managers have made their living off of hand-selecting stocks. However, it’s not a highly recommended investing strategy, especially in the long term. In addition to being risky in the first place, many speculate that it’s gotten more difficult over the years. With the rise in high-frequency trading and analytical software, it’s nearly impossible to conduct enough research to gain an edge over other investors.

However, even when technology was far less developed, many were still skeptical of stock picking strategies. Based on the efficient market hypothesis, a concept coined in 1967, it’s impossible to consistently outperform the market. Therefore, many investors prefer to focus instead on matching the market’s returns by buying a stake in a representative basket of companies, such as the S&P 500.

Timing the market rarely works

Similar to stock picking, market timing is another practice that many investment advisors warn against. You may have heard the common investment advice, “buy low, sell high.” While this strategy is effective in theory, it doesn’t work as well in practice.

Since you can't predict what’s going to happen in the market, it’s extremely easy to mistime your moves, which can have disastrous consequences. A report by Fidelity tested the results of missing the five best days in the S&P 500 on an initial investment of $10,000 between January 1, 1980 and March 31, 2020. It found that you’d miss out on $265,010, a loss of 38.6%.

Index Funds vs. Actively Managed Funds

Index funds are passively managed investments, meaning that their managers follow a more hands-off approach. Rather than strategically buying and selling in order to maximize returns, they’ll simply build a portfolio to reflect their chosen index.

Risk

On the other hand, hedge funds, as well as many mutual funds, are actively managed. This means that their portfolio managers employ strategies to increase investors’ profits. For example, they could increase their position in a company after a positive earnings report, or they might cash in on a stock’s high returns before an anticipated decline.

Similar to index funds, active funds are also made up of a variety of underlying securities. In other words, they’re fairly diversified by nature, and therefore less risky. Some argue that actively managed funds often take on more risk in an effort to beat the market. On the other hand, since they’re not built to mimic market indexes, actively managed funds may also provide a safety net in the event of a stock market crash.

Performance

Consistent with the efficient market hypothesis, it’s quite rare for actively managed funds to outperform the market over long periods of time. According to a study by Vanguard, only 18% of active mutual funds at the start of 1998 beat their benchmark indexes over a 15-year period. Additionally, the vast majority of those funds underwent extended periods of underperformance outside of the 15-year period.

Fees

Actively managed funds are also a lot pricier than their passive counterparts. Implementing a strategy requires time and resources. Therefore, investors need to cover expenses like operating and trading costs.

For this reason, actively managed mutual funds may involve expense ratios between 0.5% and 1%, or even higher. An expense ratio of 1%, for example, means that for every $10,000 invested, you’ll have to pay a fee of $100 per year. However, since index funds require very little maintenance, investors can find low-cost options at an expense ratio of 0.02% to 0.05%.

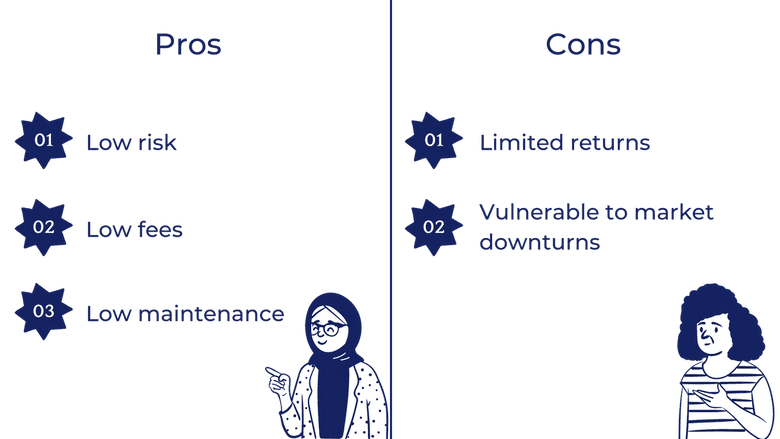

Pros and Cons of Index Funds

While index funds are a great choice for many investors, it’s important to know the upsides and downsides before making a decision.

Pros

Cons

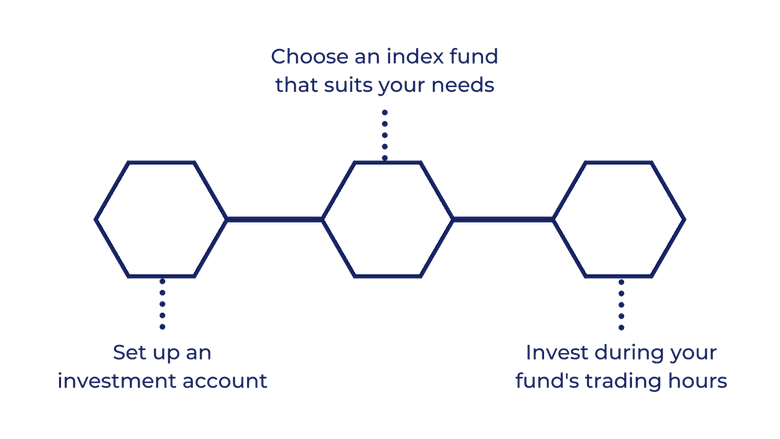

How to Invest in an Index Fund

While it may seem scary at first, buying index funds is a relatively easy process:

- Set up an investment account: You can easily set one up with an online broker like Fidelity or Charles Schwab. If you don’t have one yet, you can choose from a variety of account types, including an IRA, Roth IRA, 401(k) or brokerage account.

- Choose an index fund that suits your needs: As discussed above, there are many types of index funds and many options within those categories to choose from. Additionally, some will require a minimum initial investment, ranging from around $500 to $5,000. However, if that’s too high a commitment, it’s certainly possible to find funds without a minimum to start.

- Invest during your fund's trading hours: As previously mentioned, you can purchase ETFs at any time during market hours, just like other stocks on the market. However, mutual fund transactions will only execute at the end of the trading day.

3 Questions to Ask When Choosing an Index Fund

In order to figure out which index fund to buy, you’ll want to evaluate your own preferences and perform some basic research. Let’s discuss some questions you’ll want to ask before making your decision.

1. Which index do you want to track?

Popular large-cap indexes

Before buying an index fund, you’ll first want to consider which benchmark index you’d like to follow. Popular indexes including the S&P 500, the Nasdaq and the Dow have been known to reflect the performance of U.S. financial markets as a whole.

However, they’ve also been criticized in recent years for depending too heavily on the performance of a few large companies, primarily in the tech space. The insurance company Gallagher published insights analyzing the S&P 500’s YTD returns from September 30, 2020. It found that while the top 5-weighted companies saw returns of 40.2%, the rest of the companies in the index averaged -6.2%. In other words, while the index showed overall returns of 5.6%, an equally-weighted average would have yielded returns of -4.8%.

On the other hand, there are still a lot of upsides to choosing a popular benchmark index. For example, since they’re all widely followed, you’ll have a lot of index funds to choose from. That means you can be more selective about other qualities like price or fees.

Indexes that track a subset of the market

If you want to diversify your portfolio, you can also track a benchmark that follows a narrower subset of the overall market. For example, if you don’t want to invest in a large-cap index, you can opt for an index like the Russell 2000, which tracks small-cap companies. Likewise, if you’d like to prioritize companies with a higher book value, you might want to look into indexes like the S&P 500 value.

Single industry indexes

You can also find indexes to reflect the performance of a single industry. However, keep in mind that more obscure index funds may carry drawbacks such as limited selection and higher fees.

2. How closely does the fund track the index?

Unfortunately, not all index funds are created equal. Two funds tracking the same index won’t show the exact same returns at all times. This may be the result of various factors, including poor fund construction or high fees.

In order to find an index fund that most closely matches your benchmark index, you’ll want to compare the tracking errors across all of your options. You can do this by finding the R-squared, which will tell you how similar the fund is to the benchmark index based on how close it is to 1.

Another option is finding the fund’s beta, or volatility compared to the market, and comparing it to the benchmark index. The closer they are, the lower the tracking error.

3. What are the fees?

One of the biggest considerations for many investors in choosing an index fund is the cost. A common type of fee is the expense ratio, or the cost of owning the fund. Since this fee is charged annually, it’s important to compare in order to get the best deal for your investment.

For example, although an expense ratio of 0.5% may not seem high at first, it can add up over time. Some index funds also may charge purchase or redemption fees, which help cover the operating costs associated with buying or selling a fund. Additionally, you may face annual 12b-1 fees, which will cover the fund’s cost of marketing and distribution. These costs can’t exceed 1% of investor assets.

Index funds fees can really cut into your returns, so don’t be afraid to take some time to research your options. Many companies have started offering low-cost index funds, especially for tracking more established benchmark indexes. If you’re having trouble tracking down all of an index fund’s fees, check out its prospectus for more details.

Takeaways

Because of their diversification, lower costs and long-term benefits, index funds are a promising addition to any investor’s portfolio. However, they can vary widely based on their benchmark index, tracking errors and fees. Therefore, it’s important to do your research beforehand to figure out which index funds are right for your investment goals.

The information provided herein is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to provide tax, legal, or investment advice and should not be construed as an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or a recommendation of any security by Candor, its employees and affiliates, or any third-party. Any expressions of opinion or assumptions are for illustrative purposes only and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results and the opinions presented herein should not be viewed as an indicator of future performance. Investing in securities involves risk. Loss of principal is possible.

Third-party data has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, its accuracy, completeness, or reliability cannot be guaranteed. Candor does not receive compensation to promote or discuss any particular Company; however, Candor, its employees and affiliates, and/or its clients may hold positions in securities of the Companies discussed.